The journal Ethics just announced its AI policy. My wise friend Carlo Ludovico Cordasco has an insightful comment, in which he agrees with Ethics that an AI tool should not be regarded as a co-author, but where he also criticizes the policy for apparently rejecting better work if it was substantially generated by an AI tool. His suggested policy is summarized in this sentence: ”A version of the Ethics policy that said ‘content produced with the help of LLMs is welcome, provided authors fully endorse and are prepared to defend it, and provided their use of these tools is disclosed where substantial’ would, to my mind, capture everything that really matters.”

That is essentially my own view, as I argued in a recent blog post. While I find Carlo’s analysis largely persuasive, I wish to press further on several points.

- I am not as sure that AI tools should be excluded from co-authorship. What I am wondering is if the self-direction criterion that Carlo embraces doesn’t smuggle in an unjustified anthropocentrism. The claim that AI tools merely ”respond to prompts by exploiting patterns” could be redescribed as ”responding to environmental inputs by applying learned regularities”, which seems to me a reasonable description of human cognition as well.

- The criterion of accountability is trickier. Still, I am wondering if we are too constrained in our imaginative thinking on that point. Couldn’t institutional arrangements support AI co-authorship while preserving accountability functions? The deploying organization could bear responsibility in a manner analogous to how pharmaceutical companies are held accountable for their compounds, facing reputational damage, financial penalties, or exclusion from academic licensing when AI-coauthored work fails, perhaps supported by a registry system in which models accumulate tracked scholarly reputations. Companies might maintain a ”unit of accountability” through escrowed resources or bonded certification schemes that create genuine institutional stakes. Alternatively, and perhaps most elegantly, a human co-author could assume complete responsibility for all claims while acknowledging the AI’s substantive contribution, much as senior authors currently vouch for work conducted primarily by junior colleagues. More radically, one might reconceive the system as requiring accountability for claims rather than of authors, with verification protocols and audit systems ensuring epistemic reliability regardless of whether a responsible agent stands behind each assertion. Of course, as Carlo might object, the residual objection to all such proposals is that they satisfy only the functional requirements of accountability while omitting what some consider constitutive: a subject who experiences the weight of responsibility, feels the force of criticism, and is moved by reasons to improve. Maybe, but to me, this is an open question for the moment.

- These institutional questions connect to deeper metaphysical issues. In relation to my earlier blog post, under determinism, human agents no more ”choose which projects to pursue” in any ultimate sense than an LLM does. Both are fully determined by prior causes. The distinction between a human whose neural states were causally determined by genetics and environment, and an AI whose outputs are causally determined by training data and architecture, becomes one of degree rather than kind. The standard compatibilist response, hinted at by Carlo, that responsibility tracks reasons-responsiveness or mesh between first- and second-order desires, does provide a principled distinction, since current AI tools plausibly lack the hierarchical desire structure that Frankfurt-style compatibilism requires. However, as I see it, this is an empirical rather than conceptual point, and one that may not hold indefinitely as AI systems develop.

- On the disclosure-plus-endorsement view, I believe the disclosure requirement carries an implicit stigma, treating AI assistance as categorically different from collaborators, research assistants, or referees, thereby perpetuating a hierarchy of legitimacy. If quality and defensibility are the key considerations, the causal history should be irrelevant. Moreover, I regard the ”prepared to defend it” requirement as operationally indistinguishable from what responsible scholarship already demands. If authors understand, endorse, and can defend their work, the fact that an AI rather than a colleague or half-remembered book suggested a key analogy marks a distinction without normative difference. The pragmatic AI-positive position I find appealing would simply evaluate work on its merits, leaving the production process as private as whether one wrote sober or intoxicated, alone or in conversation. There is also a practical difficulty: when one works in genuine symbiosis with an AI tool, the attribution of contributions becomes intractable. Should a researcher maintain a log every few minutes, documenting precisely what changed following each interaction? The demand is, I fear, absurd on its face. Yet if disclosure remains vague, merely noting the symbiotic character of the process, one risks rejection at journals like Ethics that treat AI involvement as a defect requiring confession. The disclosure requirement thus places conscientious scholars in an impossible position: either engage in impractical record-keeping or accept that honest but general disclosure will count against their work.

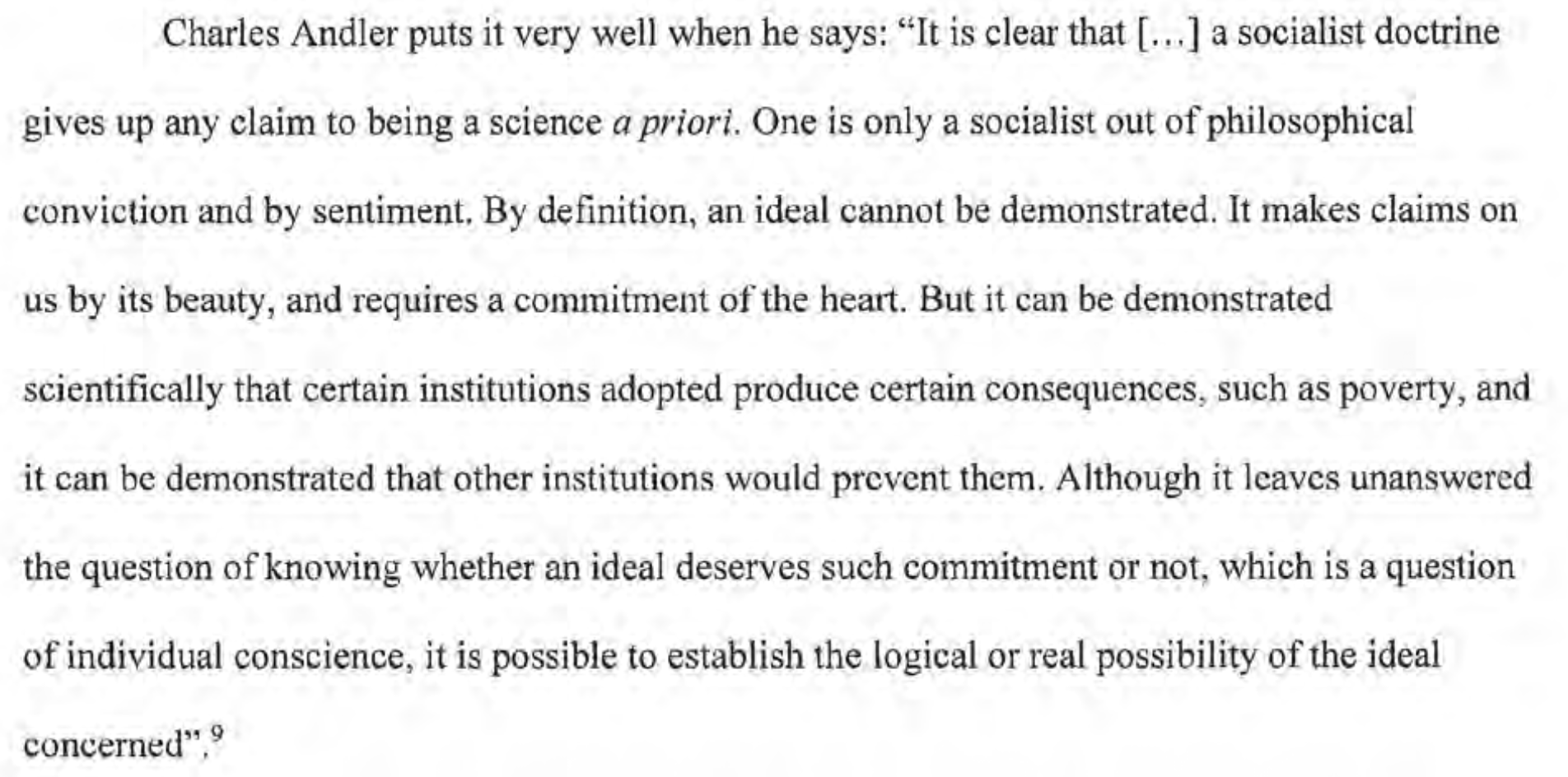

In the end, Ethics, in my view, errs toward excessive caution, treating AI involvement as a contaminant that diminishes scholarly value even when the resulting work is superior. Carlo offers the more defensible position, yet I wonder if his acceptance of the self-direction and accountability criteria may concede too much to an anthropocentrism that closer examination renders doubtful. The question of AI in scholarship is not, as I see it, fundamentally about preserving human dignity or creative purity; it is about producing reliable knowledge and advancing inquiry. A policy centered on those ends would be agnostic about productive origins and rigorous about the quality of findings.

I should add that my own thinking on these matters remains in flux, and exchanges like Carlo’s not only advance public discourse but also advance my own understanding. This ”epistemic humility” is why I view the proliferation of formal ”AI policies” with some apprehension. Such policies crystallize principles at a moment when both our conceptual frameworks and the technologies themselves are rapidly evolving. What we codify today may appear parochial tomorrow. There is something incongruous in disciplines devoted to careful reasoning adopting rigid prescriptions about the very tools of reasoning before the philosophical and technological questions are settled.

Förslag om en garanterad minimiinkomst, ofta kallad basinkomst eller medborgarlön, förs ofta fram av personer som står, eller uppfattas stå, till vänster politiskt. Det handlar trots allt om ett ambitiöst bidragssystem. Men

Förslag om en garanterad minimiinkomst, ofta kallad basinkomst eller medborgarlön, förs ofta fram av personer som står, eller uppfattas stå, till vänster politiskt. Det handlar trots allt om ett ambitiöst bidragssystem. Men

Du måste vara inloggad för att kunna skicka en kommentar.